DR. HERBERT SPIEGEL

By

Sir William Osler (1849-1919), who changed the way medicine is taught, famously said, "It is much more important to know what sort of patient has a disease than what sort of disease the patient has."

Dr. Herbert Spiegel (1914-2009) took Osler’s words to heart. Perhaps no medical figure in modern times devoted himself more zealously, and for so long a time, to the idea of "patient first" than Dr. Herbert Spiegel. The hallmark of his daring, creative and altogether extraordinary 70-year career in psychiatry was his belief that each individual’s innate personality and inner resources can be--and ought to be, by every doctor--identified and empowered as the best first step to the most effective and rapid treatment.

Consider this story out of many thousands: A woman who had been a virtual prisoner in her home for three decades because of her extreme fear of dogs came to Dr. Spiegel. At the start of the 50-minute session, he quickly determined that she had means of her own to overcome the terror. He proposed a plan of action. By herself, she conquered her affliction within a few weeks. To celebrate, her husband gave her a puppy. She named it "Spiegel." When talking about her new freedom, she thanked her doctor but gave herself the credit for the achievement. "She was perfectly right," he told me. "All I did was show her how she could focus her mind, enter a different order of consciousness, and take control."

No history of psychiatry, psychoanalysis or psychotherapy will be complete without recognizing that Herbert Spiegel was a pioneering figure who was always ahead of his time. By rescuing hypnosis from the strangling myths and misconceptions that had accumulated over centuries, he, more than anyone else, brought trance as a tool for treatment into medical acceptance and respectability.

His achievements as a clinician, researcher, innovator, teacher and author led 60 Minutes, in a report on medical hypnosis, to describe him as "the leading expert in the country, perhaps in the world."

His zest for life was greatly enhanced in 1989 by his marriage, his second, to Dr. Marcia Greenleaf, a health psychologist who was herself an authority on medical hypnosis. She became his devoted partner in searching the mysteries of the mind and developing the coping strategies patients needed to get on with their lives. She is carrying on his practice, with her own, in New York City.

From the start, in the wartime 1940s, Dr. Spiegel’s holistic approach and emphasis on an individual’s capacity for self-control foreshadowed today’s ever-expanding awareness and application of the mind-body connection in all fields of medicine.

His legendary course on clinical hypnosis at Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, where he

When he died at 95 in his Park Avenue apartment, still in demand, The New York Times told of his fame for dealing with pain, anxiety and addictions: "Broadway actors sought his help to overcome stage fright, singers to quit smoking, politicians to overcome fear of flying. For years he had his own table at Elaine’s, as well as his own place on the national stage."

Always the maverick (he deplored what he saw as psychiatry’s overly enthusiastic embrace of "pills, and more pills"), Dr. Spiegel was known to colleagues for his brilliance, generosity and humor yet he was always ready to challenge and be challenged. Even if one disagreed, it was impossible not to admire his thinking. He was an enthusiastic teacher and a prolific writer, open to new ideas and discoveries, who found satisfaction in his final years as the results of new brain research technology went far to confirm his beliefs and findings about the powers of the mind.

A few months before he died he received two awards from the Society of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis: The Best Theoretical Paper for a summation of his work, "The Neural Trance: A New Look at Hypnosis," and the Living Treasure Award for his achievements in research, clinical practice and inspirational teaching in psychiatry and hypnosis.

Dr. Spiegel’s self-confidence, never bordering on arrogance nor leading to self-promotion, rested greatly on his experience as the first American psychiatrist who was sent into combat during World War II.

Hit by shrapnel and awarded the Purple Heart, he took his battlefield experience to Long Island’s Mason General, the nation’s foremost military hospital, where his work with the mentally wounded provided exceptional opportunities to use hypnosis as way to speed recovery. In 1947, he collaborated with Dr. Abram Kardiner on the landmark book, War Stress and Neurotic Illness.

As he translated his wartime lessons to his civilian practice, Dr. Spiegel became renowned for his clarity and research about what hypnosis is and is not. The long, lurid history of mesmerism, magnetism and stage hypnotism, and fictional tales of Svengali-like mind control, deepened his commitment to teach that hypnosis is not sleep but actually quite the opposite: an exquisite awakening, with the mind focused and open to suggestions yet still in command.

Not only is "all hypnosis self-hypnosis," as Dr. Spiegel would say, but most of us are in some kind of trance or focused concentration much of the time, as when we "lose ourselves" in an absorbing book or film. Knowing that neither he nor anyone else has special powers to project on others, he did not think of himself as a hypnotist. His role was to help the individual discover untapped resources for change.

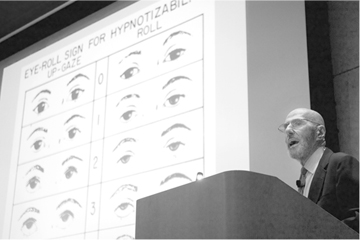

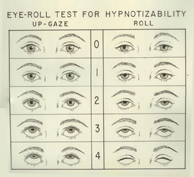

In the 1960’s, treating a woman for hysterical seizures, Dr. Spiegel noticed the patient’s eyes rolled up every time she went into a trance state. In his unique way, he combined a clinical observation with a disciplined exploration to understand it’s meaning. He proceeded to analyze thousands of patients. He discovered what he labeled, "The Eye-Roll Sign,"

He then went further in his research. He discovered that the ability to roll one’s eyes upward could signal not only the individual’s trance capacity, a fixed feature of who we are, but also corresponding personality traits. If the pupils disappear entirely for the moment, with only the whites of the eyes showing, he or she is most likely to be an "hypnotic virtuoso"—exceptionally inclined or receptive to trance experiences.

Over time, Herbert Spiegel’s discoveries led to his development of the Hypnotic Induction Profile (HIP). He used it first as a teaching tool to establish the principle that mind-body treatment is more effective when it is based on an individual’s capacity rather than a professional’s charisma, intuition or imposition. The HIP is now established as the most effective clinical means for rapidly measuring a person’s ability to use the trance experience (or perhaps be found to be incapable).

For a layman like myself, nothing about Dr. Spiegel’s work was more fascinating than his unique linkage of personality traits to the spectrum of low-to-high hypnotizability. He turned to Greek mythology to give names to the phenomena: Apollonians, Odysseans and Dionysians.

The least trance-prone individuals, perhaps more likely to be accountants than artists, are the analytical, skeptical and better organized Apollonians (the "Lows"). Their opposites, Dionysians (the "Highs"), are more emotional, less disciplined and easier to persuade. Most people are mid-range Odysseans, combining the attributes of head and heart in the broad center of the personality spectrum. He found that 75% of the population can benefit from tapping into individual capacity for trance, albeit it with different strategies and expectations.

My first encounter with Herbert Spiegel was altogether memorable—though I must be forever mindful of one of his favorite warnings, that "the only reliable thing about memory is that it is unreliable." In the mid-1970s, as an independent journalist living in the northwestern hills of Connecticut, I was caught up in the famous Peter Reilly murder case. The 18-year-old’s conviction for killing his mother most savagely was based not on evidence or motive but on a dubious confession. His apparent (and actual) innocence had turned his plight into a national cause célèbre.

Playwright Arthur Miller, leading the rescue party and knowing of Dr. Spiegel’s contributions to forensic science, asked him to appear at a court hearing seeking a new trial for the youth. After assessing the teenager with the Hypnotic Induction Profile, he delivered a cogent explanation of how the false confession from the naïve and too-trusting suspect had been obtained by the police in a classic brainwashing exercise.

Criminal justice history was made when the HIP itself, having only recently been published as a valid psychological test, became the "newly discovered evidence" necessary to meet the high standard for overturning a conviction. As I related in the book, Guilty Until Proven Innocent, the judge, the state’s future chief justice, called the psychiatrist to the bench to say that his was the most persuasive expert testimony he had heard in all his years in the law. He then overturned the "grave injustice."

I found Dr. Spiegel fascinating: the mustache, the shaven head, the delight of his story telling, his skill as a sailor, his ability to ride a powerful jumper horse

I saw Herbert Spiegel as larger than life in his field. His resurrection of clinical

hypnosis and the connection he made between hypnotizability and personality offered

insights about human nature and behavior that had value well beyond medicine. On a more practical level, in his interactions with patients, he was a liberator: giving tens of thousands a new lease on life.

His personal and professional experiences set Dr. Herbert Spiegel on a course to take the road less traveled. He had the courage to make hypnosis the centerpiece of his practice. He had the foresight to translate principles of mind-body connections into systematic treatment approaches He had a commitment to science, which led him to champion the importance of individual differences.

Although widely appreciated in his own time, as brain research catches up with his discoveries, it is likely his full recognition lies in the future.

1914-2009

Donald S. Connery

was honored with the creation of The Herbert Spiegel Lectureship in 2006, and his lectures at top medical schools around the world, introduced legions of practitioners to the art of swiftly knowing their patients, then helping them take charge of themselves. Trance & Treatment: Clinical Uses of Hypnosis, written with his son, Stanford psychiatrist Dr. David Spiegel, renowned in his own right, stands as a classic text on hypnosis.

was honored with the creation of The Herbert Spiegel Lectureship in 2006, and his lectures at top medical schools around the world, introduced legions of practitioners to the art of swiftly knowing their patients, then helping them take charge of themselves. Trance & Treatment: Clinical Uses of Hypnosis, written with his son, Stanford psychiatrist Dr. David Spiegel, renowned in his own right, stands as a classic text on hypnosis.

As a young psychoanalyst who rebelled against Freudian orthodoxy, he abandoned long-term therapy for short-term and even single-session solutions long before most of his colleagues. In his seven decades of patient encounters he may well have treated more people with problems, including many of the rich and famous, than anyone else in his profession. "I stopped counting at 50,000," he told me.

Deployed as a battalion surgeon to General Patton’s forces in North Africa, Captain Spiegel found he could use hypnosis as a psychological booster shot for traumatized soldiers.

He learned to use that modality to help the men control pain and anxiety. In the humane and efficient way that characterized the rest of his long professional career, he simultaneously made it possible for soldiers to maintain their dignity while helping the army preserve manpower. His "preventative medicine", as he called it, was the immediate response to trauma. He kept the men connected to their units instead of being transported to the rear. As he would later write, "I discovered it was possible to use trance with persuasion and suggestion to help the men return to previous levels of function."

Deployed as a battalion surgeon to General Patton’s forces in North Africa, Captain Spiegel found he could use hypnosis as a psychological booster shot for traumatized soldiers.

He learned to use that modality to help the men control pain and anxiety. In the humane and efficient way that characterized the rest of his long professional career, he simultaneously made it possible for soldiers to maintain their dignity while helping the army preserve manpower. His "preventative medicine", as he called it, was the immediate response to trauma. He kept the men connected to their units instead of being transported to the rear. As he would later write, "I discovered it was possible to use trance with persuasion and suggestion to help the men return to previous levels of function."

an immediate indicator of a person’s more-or-less capacity for focused concentration, a form of dissociation, that, amazingly, had never before been studied and understood.

an immediate indicator of a person’s more-or-less capacity for focused concentration, a form of dissociation, that, amazingly, had never before been studied and understood.

on his time off from his practice. We became friends. I was intrigued by the role he had played in the famous case of Sybil, serving as one of her doctors yet refusing to endorse the portrait of her supposed multiple personality disorder as portrayed in the popular book and film. I twice attended his hypnosis course at Columbia and ended up writing a book, The Inner Source: Exploring Hypnosis with Dr. Herbert Spiegel,

on his time off from his practice. We became friends. I was intrigued by the role he had played in the famous case of Sybil, serving as one of her doctors yet refusing to endorse the portrait of her supposed multiple personality disorder as portrayed in the popular book and film. I twice attended his hypnosis course at Columbia and ended up writing a book, The Inner Source: Exploring Hypnosis with Dr. Herbert Spiegel,  about his adventures and discoveries.

about his adventures and discoveries.

Dr. Herbert Spiegel 1914-2009

BIO